The German automotive industry is currently regarded as a prime example of an industry in upheaval: carmakers are investing billions in the design of new electric cars and the construction of their production facilities. As part of this strategy, a major German carmaker announced its intention to produce 22 million so-called Battery Electric Vehicles (BEV) over the next ten years.Will the global cobalt reserves be sufficient to keep pace with the ambitious plans?

Cobalt as a decisive component of modern battery cells

When designing electric cars, all automobile manufacturers without exception are currently relying on lithium-ion-batteries (LIB). From a technological point of view, there is currently no alternative to lithium-ion batteries. This is due to their high energy density, comparatively low weight and slow self-discharge. As an analysis by Energy Brainpool has already shown, it is estimated that the currently available and economically degradable lithium reserves will last until 2050 to meet global demand.

When choosing the cathode material, many manufacturers (e.g. Samsung, LG Chem) currently rely on nickel-manganese-cobalt-cathodes (NMC-cathode). NMC cells offer significant advantages over other types of cathodes. Above all they have a long life cycle and the absence of memory (loss of transit time due to frequent partial discharges). In fact, most of the remaining manufacturers (Tesla/Panasonic, Lishen Tianjin, BYD) plan to switch to low cobalt NMC cathodes in the future.[1] [2]

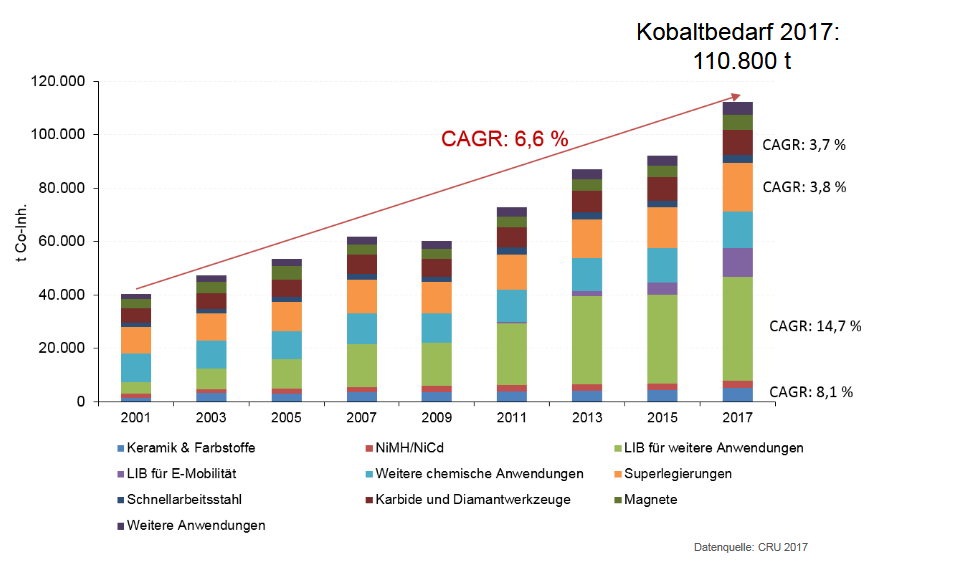

Figure 1: development of the demand and the usage of cobalt from 2001 to 2017 [Source: German Mineral Resources Agency][3]

Instability of the main producer country leads to high price volatility of cobalt

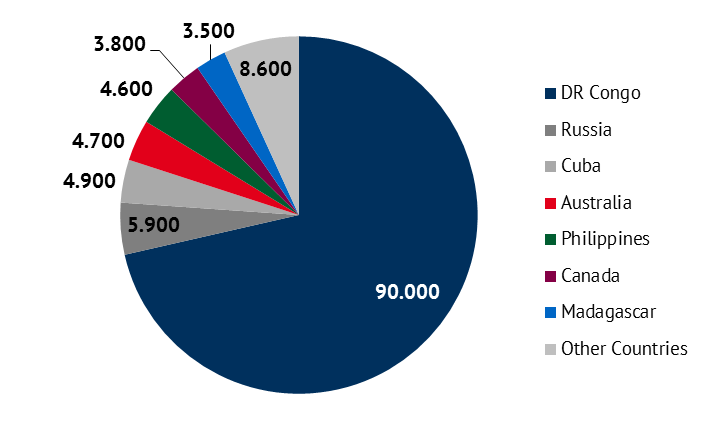

In 2018, more than 71 percent of the 126,000 tons of cobalt mined came from the Democratic Republic of Congo. A further 22 percent was distributed comparatively evenly among Russia, Cuba, Australia, the Philippines, Canada and Madagascar (Figure 2).

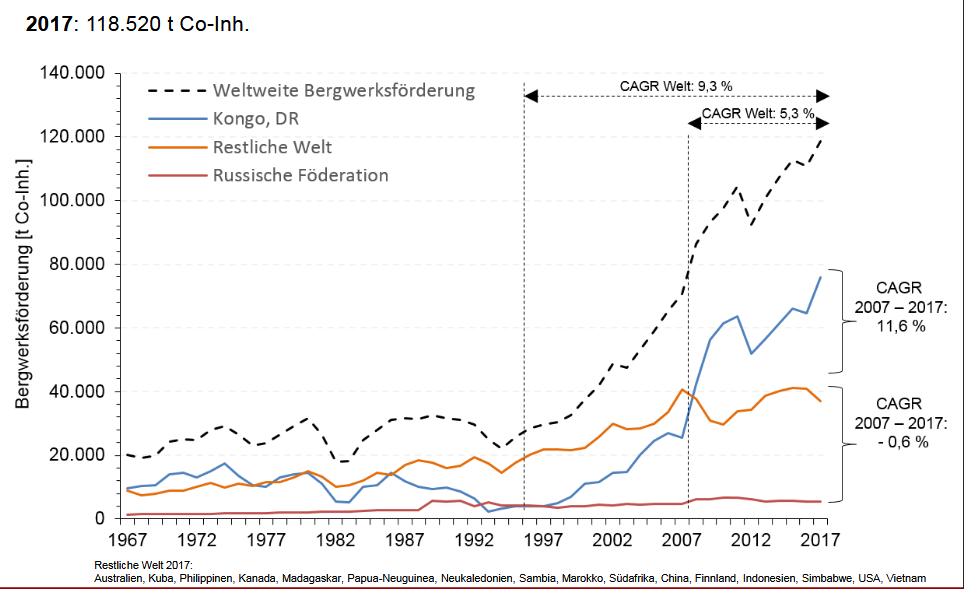

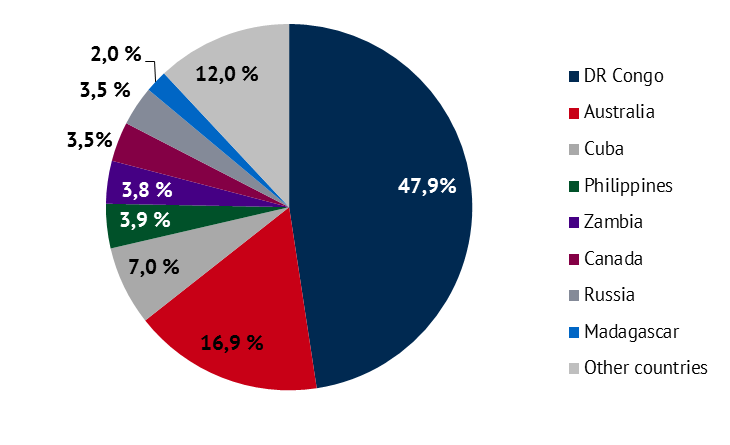

If we look at the data on global reserves, the important role of the DR Congo is even clearer. Of the approx. 7.4 million tons of cobalt that is economically exploitable worldwide, almost 48 percent is located in the Central-African country. It is followed by Australia (17 percent), Cuba (7 percent) and a few other countries with smaller proportions below 5 percent (Figure 3).In addition to the largest reserves and the largest production volume, the mining volumes in the DR Congo also showed the strongest growth rates in recent years. Cobalt production in the rest of the world fell by an annual average of 0.6 percent between 2007 and 2017. On the other hand, the DR Congo recorded an average growth rate of 11.6 percent over the same period (Figure 4).

Cobalt is one of the most expensive material for battery production. It has been subject to strong price fluctuations in recent years. Since January 2017, the price has fluctuated between 25,000 and 80,000 EUR/tons. The strong fluctuations can partly be explained by the fact that cobalt rarely occurs in its pure form. The raw material is mainly extracted as a by-product from nickel (37 percent) and copper (61 percent) mining. [5]

Figure 4: Cobalt Offer Mine Production 1976 – 2017 (In German only) [Source: German Mineral Resources Agency [7]

In addition, most of these non-industrial mining sites are located in the politically and economically unstable DR Congo. It can be assumed that in the past these factors were often the reason for the pronounced price volatility with significant price peaks.

E-mobility as a main driver of Cobalt demand

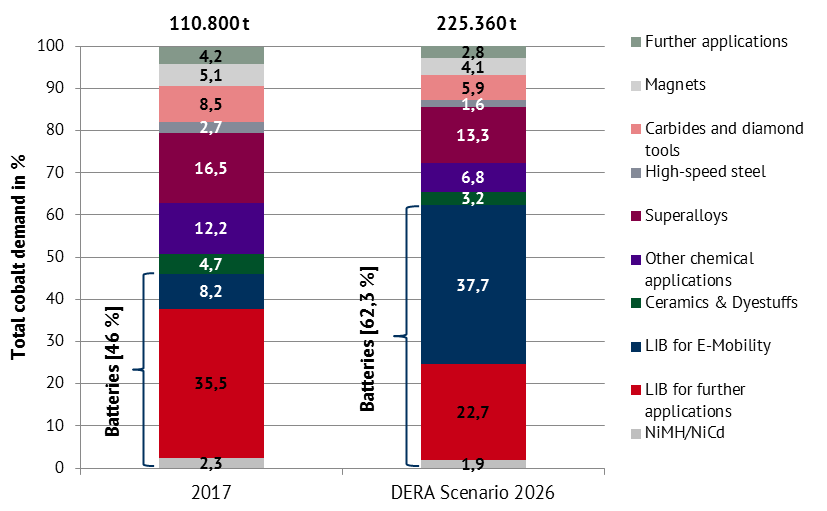

Supply and demand are considered to be one of the main drivers for the cobalt price. The progressive scenario of the German Mineral Resources Agency (DERA) on cobalt demand assumes that world demand will grow to 225,000 tons per year by 2026. Of this, 140,000 metric tons or 62 percent can be attributed to battery production. According to the scenario, e-mobility will increase its share of world demand from 8.2 percent in 2017 (9,000 tons) to 37.7 percent in 2026 (85,000 tons) (Figure 5). As a result, it can be described as the main driver of cobalt demand in the coming years.

Volkswagen alone, as the automobile manufacturer with the highest turnover, plans to invest EUR 30 billion in e-mobility by 2023. If the Group were to actually produce 22 million BEV in the next ten years as planned, its cobalt need would be around 30,000 tons/year.[10] Volkswagen would thus be responsible for 13 percent of global demand in 2026. In other words, the company would demand 35 percent of the cobalt required for e-mobility.

On the supply side, DERA expects the cobalt supply to increase to 222,100 tons by 2026. This would be the result of extensions to existing mines, the resumption of old mines and the construction of new ones.In the medium term, experts expect a slight shortfall in cobalt demand. For this reason, unlike most other commodity markets, the cobalt market can be expected to remain a supply market rather than a demand market. As mining companies and producing countries can choose their customers, customers face additional supply and price risks.

Growing influence of China as a key player in e-mobility

China’s great ambitions to play a leading role in e-mobility also make it a major player in the cobalt market. In 2016, the country was importing 54,000 tons of cobalt and dominated large parts of the processing industry, from mined cobalt ore to the finished lithium-ion battery. In fact, China’s share of global cobalt refinery production in 2017 was 70,000, 59.5 percent. [12]

It is not uncommon for the aforementioned price and supply risks to be cited as the reason for the sharp increase in Chinese influence on resource-rich African countries. In the difficult cobalt market environment of 2016, China secured 53 percent of DR Congo’s cobalt production (48,000 tons).

On top of that, in the same year China Molybdenum Co., Ltd. acquired a 56 percent stake in the Tenke Fungurume Mine for USD 2.65 billion. This mine is currently the largest copper mine in Africa.[13] The current position allows China to exercise more control over both prices and supply chains.

Long-term relaxation of the cobalt market in sight

Despite the expected shortage on the cobalt markets in the short term, there are also a number of reasons that indicate that the situation will ease in the medium to long term.

In purely mathematical terms, the 7.4 million tonnes of reserves of cobalt alone would suffice to secure an average demand for cobalt of 300,000 tonnes/year until 2042. The price increase seen in the past should lead mining companies and producing countries to invest in primary production in order to develop the known reserves.

In addition to these land-based reserves, cobalt also occurs in two other locations: in crustal form in primary crustal zones and in manganese nodules in the Clarion Clipperton Zone in the Central Pacific. These as yet unused cobalt deposits in the deep sea are estimated to total 94 million tonnes. [14] If these are added to the onshore reserves, the demand for cobalt would be secured up to the year 2356.

Use of cobalt in batteries is decreasing

With regard to the demand for cobalt, it must also be borne in mind that the use of cobalt per battery cell has been declining for years. While nickel-manganese cobalt cathodes (NMC cells) with a mixing ratio of 1/1/1 are a phase-out model, modern NMC cells already have a mixing ratio of 5/3/2 (50 percent nickel, 30 percent manganese, 20 percent cobalt).

More distant forecasts even assume that by 2026 25 percent of all cathodes will manage with a mixing ratio of 8/1/1. That means that the same amount of cobalt can generate 3.3 times as much battery capacity (compared to NMC cells with a mixing ratio of 1/1/1). [15] [16]

Recycling potential of cobalt is increasing

Another elementary goal of battery cell research is to exploit the potential of cobalt reserves in the economic cycle through recycling. As e-mobility progresses and the number of battery cells increases, it is clear that the potential of subeconomic reserves is also growing every year.

Considering that a battery cell has a service life of about 16 years (on average 8 years as energy storage for BEV, and 8 years in Second Life as stationary storage)[17], their subeconomic cobalt reserves could be reused at the end of their lifetime. The German Mineral Resources Agency assumes that by 2026 13,000 tons of cobalt. That means that 5.8 percent of the world’s supply, will come from the recycling of old battery cells. [18]

Summary and prospect

In summary, it can be said that in the short term there will be a strong demand for the currently available cobalt reserves. For manufacturers of electric cars and other battery cell producers one thing will be significant. In practical terms it will be crucial to hedge themselves with long-term supply contracts against price and supply fluctuations in the mainly from the DR Congo dominated market.

However, due to the currently lucrative prices and rising demand, it is to be expected that the largest producer countries will massively increase their primary production of cobalt in the long term. In the medium term, delays in mine projects could still lead to small supply deficits and thus price increases. On the other hand, the efficient use of cobalt in battery cells is likely to be further researched and developed by manufacturers. This will have a dampening effect on overall demand. As the number of old batteries increases, the recycling of battery raw materials should also become more scalable and thus more lucrative.

It can be therefore expected that the potentially strongly growing supply of cobalt will lead to prices stabilizing at a low level in the long term. In the long term, extreme price peaks caused by a shortage of supply should be a thing of the past.

[1] https://www.batterien.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/batterien/de/documents/Allianz_Batterie_Zellformate_Studie.pdf , Page 5

[2] https://www.scientia.global/highest-energy-li-ion-battery-unlocking-potential-silicon-anode-nickel-rich-nmc-cathode/

[3] https://crm.saena.de/sites/default/files/civicrm/persist/contribute/files/2018_12_03%20Rohstoffmonitoring_Kobalt.pdf, Page 8

[4] https://investingnews.com/daily/resource-investing/battery-metals-investing/cobalt-investing/top-cobalt-producing-countries-congo-china-canada-russia-australia/

[5] https://www.deutsche-rohstoffagentur.de/DE/Gemeinsames/Produkte/Downloads/Commodity_Top_News/Rohstoffwirtschaft/53_kobalt-aus-der-dr-kongo.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2

[6] https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/38455/umfrage/weltweite-reserven-an-cobalt/

[7] https://crm.saena.de/sites/default/files/civicrm/persist/contribute/files/2018_12_03%20Rohstoffmonitoring_Kobalt.pdf, Page 20

[8] https://crm.saena.de/sites/default/files/civicrm/persist/contribute/files/2018_12_03%20Rohstoffmonitoring_Kobalt.pdf

[9] https://crm.saena.de/sites/default/files/civicrm/persist/contribute/files/2018_12_03%20Rohstoffmonitoring_Kobalt.pdf

[10] https://www.handelsblatt.com/meinung/kommentare/kommentar-volkswagen-geht-mit-seiner-elektro-strategie-voll-ins-risiko/23974628.html

[11] https://crm.saena.de/sites/default/files/civicrm/persist/contribute/files/2018_12_03%20Rohstoffmonitoring_Kobalt.pdf, Page 14

[12] https://crm.saena.de/sites/default/files/civicrm/persist/contribute/files/2018_12_03%20Rohstoffmonitoring_Kobalt.pdf, Page 21

[13] http://www.chinamoly.com/05news/DOC/CMOC_Press_Release_(English)_vF.pdf

[14] https://worldoceanreview.com/wor-3/mineralische-rohstoffe/kobaltkrusten/

[15] https://www.batterien.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/batterien/de/documents/Allianz_Batterie_Zellformate_Studie.pdf

[16] https://cleantechnica.com/2018/06/17/teslas-cobalt-usage-to-drop-from-3-today-to-0-elon-commits/

[17] https://mobilitymag.de/batterien-second-life-elektroautos/

[18] https://crm.saena.de/sites/default/files/civicrm/persist/contribute/files/2018_12_03%20Rohstoffmonitoring_Kobalt.pdf, Page 25

What do you say on this subject? Discuss with us!