In recent years, the regulatory map of the energy industry has become increasingly complex. Especially for coal-fired power plants, some inconsistencies and contradictions have crept in during the course of parallel legal processes. Here is an attempt to shed some light on the situation.

In the energy triangle of economic efficiency, security of supply and environmental protection, the component on environmental and climate protection has gained in importance – but not without resistance. Many regulations and laws on the energy system have been edited over the last years. This was done in order to find a better compromise for complex issues which are relevant to society.

Above all, the combustion of lignite and hard coal is known to cause carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, but other environmentally harmful gases are also emitted. Legislators at the European Union (EU) level reviewed the emission limits for large-scale combustion plants (i.e. especially power plants) in 2017. These limits include nitrogen oxides, sulphur dioxide, particulate matter and, for the first time, mercury.

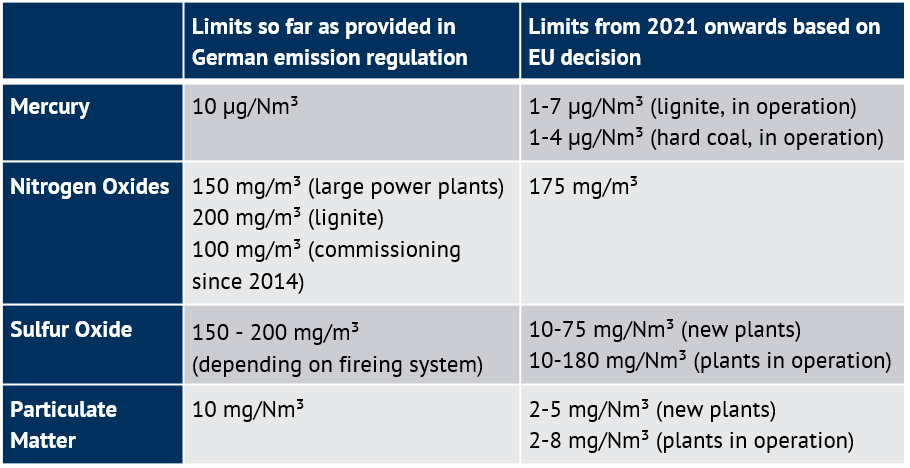

The new limits (cf. Table 1) were adopted on July 31st, 2017 as implementing provision 2017/1442 against the votes of the German government, Poland, Bulgaria and the Czech Republic. Subsequently, these limits must be complied with from August 2021. The German government considered the limits, e. g. for nitrogen oxides, to be too strict and “inappropriate”. It based its arguments on assessments by the Federal Environmental Agency („Umweltbundesamt“, UBA). [1]

New limits throughout the EU as of 2021

Table 1: emission limits as annual average for power plants >300 MW_th (Sources: 13th BImSchV [2]; Implementing Provision (EU) 2017/1442, Chapter 2.1 [3]; Tebert 2018 [4])

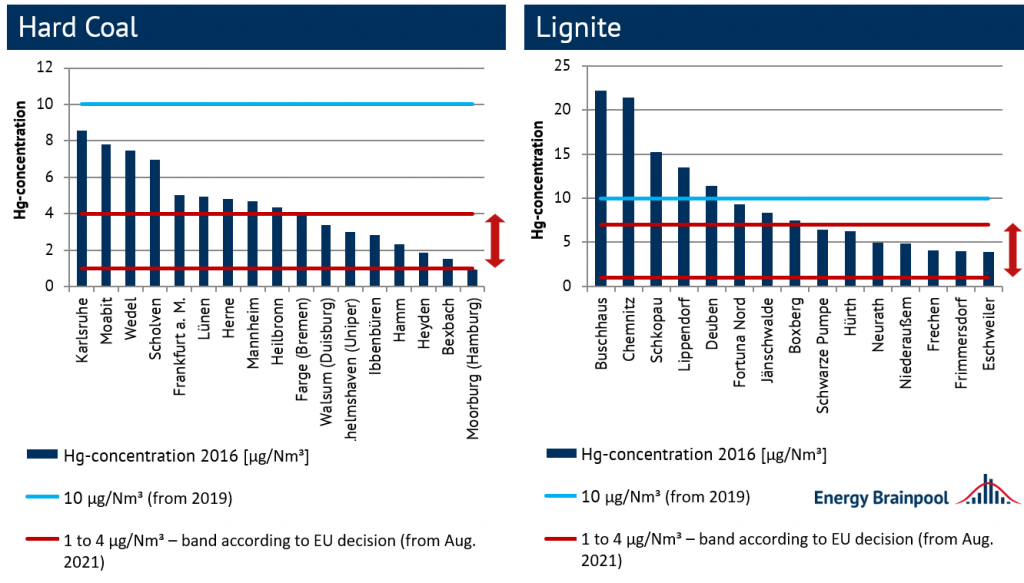

Figure 1 shows that some of the German hard coal and lignite-fired power plants comply with the new limits, while some exceed them significantly. (The Buschhaus and Frimmersdorf power plants are now part of the security of supply reserve („Sicherheitsbereitschaft“) so they are no longer in operation. In November 2019, the City of Leipzig decided to phase out district heating from the Lippendorf power plant by 2023.)

Figure 1: mercury emissions of selected power plants and future limits (Source: E-PRTR, 2016 [5], own illustration)

Instead, the federal states of Brandenburg, North Rhine-Westphalia and Saxony urged the then Federal Minister of Economics, Mrs. Zypries, to take action for annulment to the EU. She refused to do it. In February 2018, the Free State of Saxony joined the coal associations Debriv and Eurocoal as well as the power generating companies Leag and Mibrag in filing a lawsuit against the “unlawfully introduced EU requirements”. [6]

Coal phase out decided in Germany

In June 2018, the commission “Growth, Structural Change and Employment” (also known as the “Coal Commission”) was set up to find a broad political and social compromise on how to phase out power generation from coal. These negotiations took place under the impression of massive climate protection protests at the Hambach Forest (near Cologne) in autumn 2018. Eventually, it ended with the publication of the final report on January 26th, 2019. The report describes a two-stage coal phase-out (2030 and 2038). Additionally, it names a requirement of 40 billion euros to finance the structural change in the lignite regions (1.3 billion plus 0.7 billion euros per year over 20 years, p. 104).

In Chapter 3.2.1, this final report picks up the above-mentioned EU decision on emission limits for coal-fired power plants. Furthermore, it states that most German power plants do not meet the emission limits for nitrogen oxides and mercury. For example the EU implementing provision has not yet been transferred into German law, and a legal action against this decision would still be pending.

In fact, this legal action by the coal associations was already rejected as inadmissible in December 2017. It is questionable whether the authors of this chapter were not up to date or whether this fact was ignored on purpose.

Draft for Climate Action Plan 2050

In February 2019, the German Federal Ministry for the Environment („Bundesministerium für Umwelt“, BMU) published a draft of a climate protection framework law („Klimaschutzrahmengesetz“). In it, the climate protection targets for the years 2030, 2040 and 2050, which were already laid down in the Climate Protection Plan 2050, were to be made legally binding. Another special novelty was that the relevant ministries should be responsible for meeting the emission targets of their respective sectors (energy, agriculture, transport, buildings). In addition, the ministries should finance corresponding programmes and measures as well as the purchase of emission certificates (in the event of exceeding the target) from their own budgets.

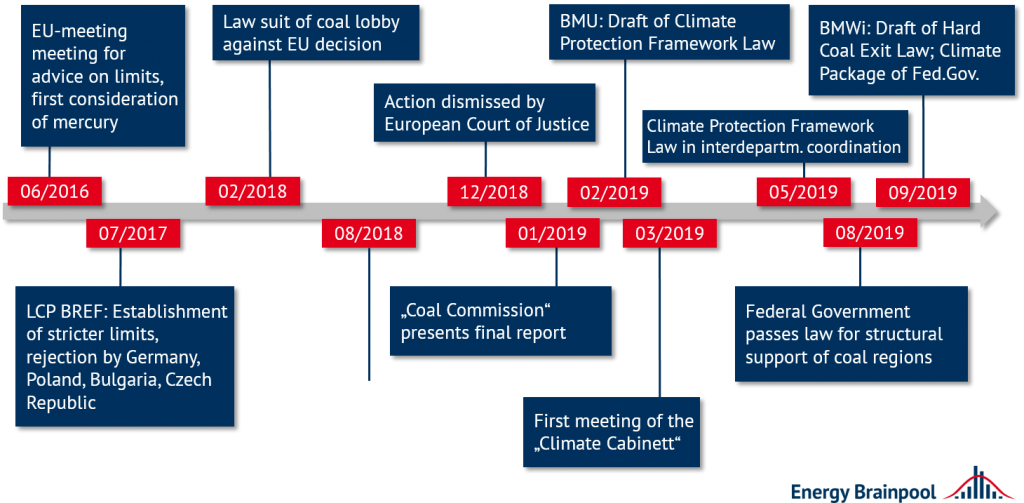

Figure 2: timeline of some milestones in climate protection legislation in Germany (Source: Energy Brainpool)

In August 2019, the BMU announced that it would deal with the transfer of the EU implementing provision for the emission limits of large-scale combustion plants into national law. This in turn prompted several industry associations, including BDEW, VKU, BDI and IG BCE, to write a joint “fire letter”.

The authors refer to the introduction of the final report of the Coal Commission. In detail, this means that the German government should ensure that changes in “environmental and planning law do not jeopardise or undermine the results achieved by the Commission”. Furthermore the authors claim that for such low emission limits, as decided by the EU, no applicable technologies are available on a large scale. [7]

Turf war on several levels

The question is whether a decision of a national commission can take precedence over the EU implementation provision adopted by majority vote. And who will prevail in the turf war on the subject of climate protection: the BMU led by the social democrats (SPD) or the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Industry („Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie“, BMWi), led by the Christian conservatives (CDU).

To infuse the coal phaseout as described by the Coal Commission into a law, the BMWi has been working on a respective law for some time now. To be more precise, the law describes how coal-fired power generators are to be taken out of the market step by step by means of decommissioning tenders. A draft was published in September 2019. The cabinet’s decision was aimed at for November, but then postponed again. Overall, the draft describes that, if the tenders (i. e. the market-oriented approach) do not work, bans on electricity generation will apply as of 2023 in order to comply with the requirements of the final report of the Coal Commission.

This decommissioning tender is reminiscent of the tenders for various types of reserve power plants contained in paragraph 11 and 13 of the Energy Industry Act („Energiewirtschaftsgesetz“, EnWG) as amended by the Electricity Market Act 2016 („Strommarktgesetz“). Power plants can be transferred to a grid reserve (§ 13d EnWG), a capacity reserve (§ 13e EnWG) or a lignite reserve (security of supply reserve, „Sicherheitsbereitschaft“, § 13g EnWG) via various mechanisms.

With regard to availability, the regulation has different requirements on these reserve power plants . For example, coal-fired power plants in “security of supply reserve” have a lead time of ten days plus 24 hours to start up before they have to provide the required rated power output.

Milestone “German Climate Package”

One of the last milestones in this series of new regulations was the “climate package”, which the German „Climate Cabinet“ adopted on September 20th, 2019 and then passed on to the Federal Cabinet. No sooner than March 2019, the Climate Cabinet met for the first time. It consists of the ministers of the ministries concerned and is headed by the Federal Chancellor.

The Climate Cabinet is an idea from the Climate Protection Framework Act of the BMU and was directly put into practice. In summary, the following Energy BrainBlog articles provide an overview of the resolutions on the climate package: Part 1: Objectives and measures, Part 2: CO2 price, Part 3: Buildings and transport. However, the most recent declarations of intent and draft laws have yet to be transformed into legally binding laws.

What does the market say?

Another perspective is that of the market. Continuously, Energy Brainpool monitors the electricity market and conducts various analyses. According to this, it may happen soon that the question of how the shutdown of lignite-fired power plants could be regulated by law will no longer arise. Instead, the electricity market with its prices and costs could become a reason for coal-fired power plants becoming unprofitable and being shut down by the operators themselves.

The reason for this would be the so-called “fuel switch”, which means that in the merit order of the electricity market, coal-fired and gas-fired power plants switch position. Basically, the merit order is sorted according to marginal costs, important influencing factors are the gas price and the CO2 price. Until now, the CO2 price for large power plants has risen significantly in the last two years and between April and October 2019 it was mostly more than 25 EUR/tonne.

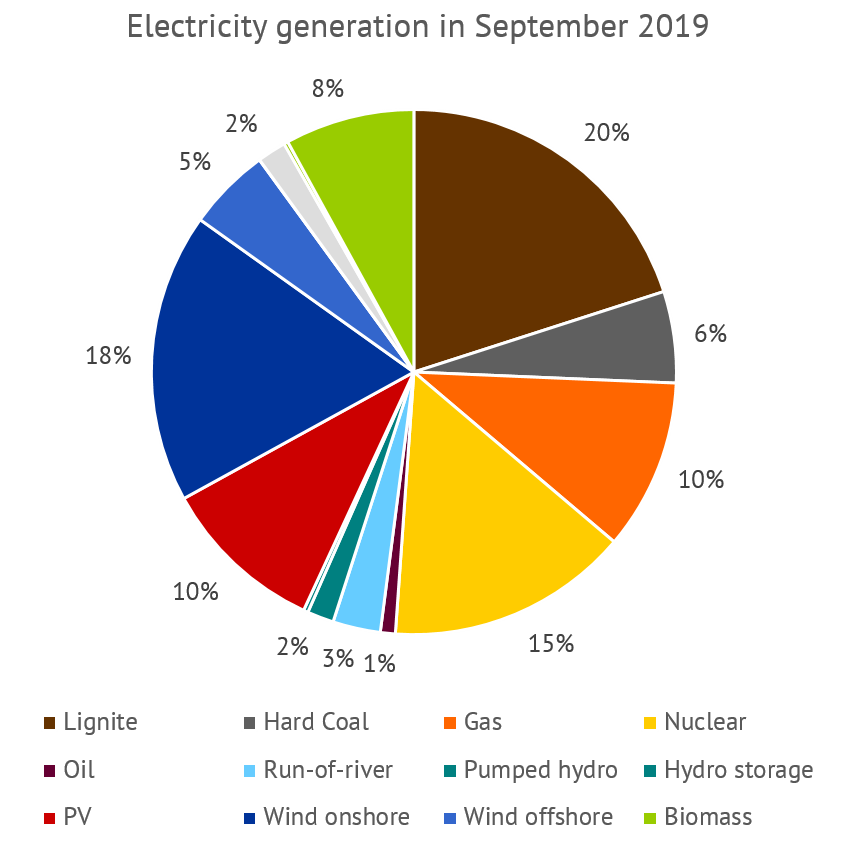

At the same time, the gas price has fallen to a historical low of around 10 EUR/MWh (thermal). As a result, for example, in September 2019 particularly efficient gas-fired power plants had lower marginal costs than older, inefficient coal-fired power plants with high CO2 emissions. The share of lignite and hard coal in electricity generation fell to 26 percent, while gas-fired power plants accounted for 10 percent. (cf. Figure 3; you can find more details in our Market Review for September.) For comparison: in 2018, the share of hard coal and lignite was 38 percent and that of gas 7.4 percent. [8]

Figure 3: shares of electricity generation in Germany in September 2019 (Data source: Entso-E Transparency [9], own illustration)

How do CO2 prices affect the price of electricity?

In an earlier blog article, the effect of CO2 prices on electricity prices is already well explained. There is also a merit order with individual power plants, which illustrates the fuel switch at different CO2 prices.

If CO2 prices continue to rise, the full load hours of coal-fired power plants will continue to decrease. By comparison those of gas-fired power plants will increase. Older lignite-fired power plants would then no longer be economically viable from 2022 at the latest, according to analyses by Energy Brainpool. The higher CO2 emission factor for lignite-fired power plants unfolds a great leverage on short-term marginal costs with rising CO2 certificate prices. Newer power plant units, on the other hand, would pay off for most of the decade ahead.

Conclusion

So the question remains: Who will be quicker to phase out coal – the market or new regulation? Since the CO2 price ultimately also depends on European policy and the rules of the emissions trading system, political decisions do have an impact on the market.

The price of CO2 certificates is difficult to predict due to many uncertainties in demand. Nevertheless, many climate researchers see the CO2 price as a key element in reducing CO2 emissions. Great Britain, for example, shows how effective such a policy instrument can be. There, the share of coal-fired electricity generation is now less than 5 percent.

The tenders for the decommissioning of coal-fired power plants planned by the Federal Government have the advantage of being easier to plan (provided the tenders are successful). But the question remains as to whether it is justified that power plants that no longer comply with the Europe-wide limits should be compensated for their decommissioning.

The showdown between the legal framework for environmental and climate protection on the one hand and price developments on the electricity market on the other will continue in the coming years. The game for coal-fired power plants is at least not over yet.

Sources

[1]: Kleine Anfrage der Grünen, Drucksache 18/12337, http://dipbt.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/18/123/1812337.pdf

[2]: 13. BImSchV, https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bimschv_13_2013/13._BImSchV.pdf

[3]: Durchführungsbeschluss (EU) 2017/1442, Kapitel 2.1, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/DE/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32017D1442&from=DE

[4]: Tebert, 2018, https://www.bund.net/fileadmin/user_upload_bund/publikationen/kohle/kohle_stickoxid_emissionen_gutachten.pdf

[5]: European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (E-PRTR), https://prtr.eea.europa.eu/#/home

[6]: Jörg Staude / Frankfurter Rundschau, 18.08.2018, https://www.fr.de/wissen/deutsche-kohle-gate-10969214.html; Susanne Götze, Jörg Staude / Klimareporter, 18.08.2018, https://www.klimareporter.de/strom/rechtsbruch-bei-kohle-grenzwerten

[7]: Klaus Stratmann / Handelsblatt, 23.08.2019, https://www.handelsblatt.com/politik/deutschland/energieversorgung-durch-neue-grenzwerte-droht-ein-kohleausstieg-durch-die-hintertuer/24931966.html?ticket=ST-22945891-Btz5gWvtY0oQPubbh9fq-ap5;

Christian Schaudwet / Tagesspiegel Background, 26.08.2019, https://background.tagesspiegel.de/neue-schadstoff-grenzwerte-beunruhigen-kraftwerksbetreiber

[8]: Fraunhofer ISE, Öffentliche Nettostromerzeugung in Deutschland 2018: Erneuerbare Energiequellen erreichen über 40 Prozent, 2.1.2019, https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/de/presse-und-medien/news/2018/nettostromerzeugung-2018.html

[9]: ENTSO-E Transparency Platform, https://transparency.entsoe.eu/

What do you say on this subject? Discuss with us!