Why is it that the proportion of new registrations of electric vehicles is so low compared to that of combustion engines? The fear of a low range is still making the rounds. And user unfriendliness is common in the jungle of charging cards and tariffs. But is the worry of not arriving justified? What solutions are there to simplify the charging process? All this in the second part of our series on e-mobility.

In order to find out whether the fear of a low range is justified (also a survey by E.on), we first go into the charging possibilities and the status of the charging network today. We also assess how far the actual state is still away from the demand that would result from a market ramp-up.

The data situation on charging stations and charging points for electric mobility still leaves much to be desired. Often no distinction is made between a charging station, which of course can have several charging points, and a charging point. The comparability of charging facilities is further impaired by the fact that some charging facilities can be used publicly, others partially publicly and others only privately.

At the Federal Network Agency, operators of publicly accessible normal and fast charging points have to register these according to the Charging Column Ordinance (LSV). An overview can be found on the BNetzA charging point map (source: BNetzA). The association BDEW also offers a charging point register. It contains the public and partially public charging points available in Germany, which can also be displayed as a map (source: BDEW).

At the end of July 2018, BDEW recorded 13,500 public and 6,700 semi-public charging points, while the BNetzA recorded 5,400 public charging points. The major difference can be explained, among other things, by the fact that public charging points are defined differently within the two registers and that normal charging points below 22 kW, which were installed before the LSV came into force, no longer have to be reported to the BNetzA. Other providers of charging post registers on the European level are GoingElectric, LEMnet or e-stations.

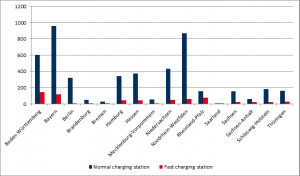

Figure 1 shows the number of charging stations per federal state according to the BNetzA charging point register. Normal charging station have a charging capacity of up to 22kW, while anything beyond that is referred to as fast charging station.

The southern federal states and North Rhine-Westphalia are well above average. The density of charging stations is also very high in the city states, but very low in the eastern German states. According to the coalition agreement, at least 100,000 charging points for electric vehicles should be available by 2020.

Fast charging points should even account for one-third of this figure. The Federal Charging Infrastructure Programme is also intended to help set up around 15,000 new charging points throughout Germany. They will be funded with a total of 300 mil. EUR.

In some cases, however, there are also indications that the currently installed charging points are not being used to capacity at all and that there is therefore no shortage. E.on, the research organisation Transport&Environment and BDEW consider the current charging infrastructure to be sufficient. According to E.on, only 4.5 cars use one public charging station.

However, the average says relatively little about the regional distribution of the charging stations (see Figure 1). To put it in a nutshell: if an electric motorist from Munich wants to go to Saxony, but can’t find any charging points in northern Bavaria, for example, then the road towards a balanced charging infrastructure is still a long way off.

Tariff jungle while charging

The often lamented chaotic tariff structure for charging e-cars does not exactly make the use of charging points user-friendly. Charging point operators compete with various billing service providers for the few e-mobilists so far.

In order to be able to charge an e-vehicle anywhere in Germany, several charging cards and registrations are required. The costs for charging also vary greatly depending on which charging station operator’s network the vehicle is being recharged.

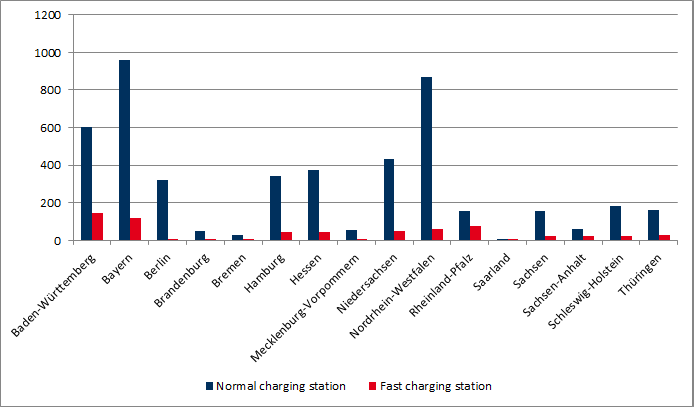

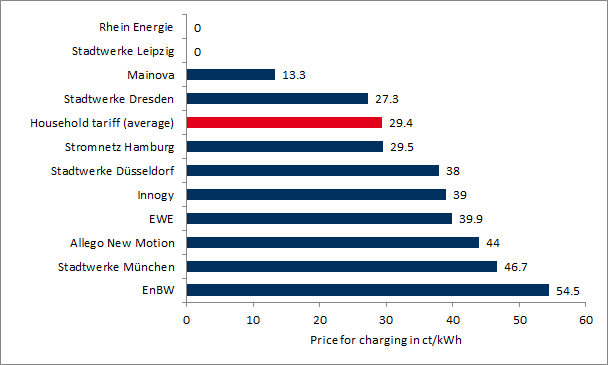

The green electricity supplier Lichtblick has published an interesting analysis in this regard. Main points: Expensive and opaque tariffs, a “chaotic patchwork” of charging infrastructure and “a Babylonian tangle of cards, apps and payment systems”. Figure 2 shows the costs for charging one kWh via a public charging station with 11 kW without a contract for a selection of providers (according to: Lichtblick).

Everything is included, from 0 ct/kWh to over 50 ct/kWh, with the majority of providers charging more than for the average price of one kWh for a household. A small and generalised calculation example illustrates the costs for combustion engines and electric cars in operation over 100 kilometres. The rather conservative assumption from the previous part of the series of 25 kWh per 100 km for an electric car is compared with a consumption of 6 litres per 100 km for a combustion engine.

Furthermore, it is assumed that the cost of charging with the average household tariff and the price of one litre of fuel is EUR 1.5. It follows that the cost of charging an e-car for 100 kilometres is EUR 7.35 for a 100 kilometre journey. The the same trip with a car with combustion engine costs EUR 9.

Billing is a problem

Another problem area in the area of charging infrastructure is billing exact kWhs. Only a small group of suppliers have charging stations that comply with calibration law and are certified by the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) and can and are therefore able to charge their customers on a certified kWh basis.

Many other providers calculate their prices for charging processes according to time period or flat-rates. About a dozen providers are currently in the PTB conformity assessment procedure (source: Bizz Energy). As long as there are different billing procedures and modalities, the charging process remains opaque for customers.

This is often ignored: The energy industry regulation currently stops after the charging. By definition, a measuring point still has a fixed location, so the final consumer of the electricity is the charging device and not the electric vehicle. On the part of the charging pillar operators, it is therefore “mere” service for customers if they are billed according to kWh.

Conclusion

In order to guarantee a seamless charging infrastructure in Germany, the geographic distribution of charging stations certainly still needs to catch up. However, the expansion of the charging stations is in progress and is being promoted politically.

The situation regarding charging tariffs is still opaque and often not customer-friendly. However, the standardisation for kWh-accurate billing seems to be making progress and thus enabling the comparability of charging service providers. In the next part of the series on e-mobility, we will look in more detail at the business models and the various players in the field of e-mobility.

What do you say on this subject? Discuss with us!