Climate conferences or the COPs are the most important international forum for negotiations on climate change and greenhouse gas emission reductions. How did the climate negotiations fare since the famous Paris Agreement in 2015? What has been agreed on during the last COPs and what is in store for the coming climate conferences? This article sheds some light on those issues as well as on the emission reality on the ground.

The UNFCCC framework

Since the inception of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988 and the adoption of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992 much has changed in international climate negotiations as well as in the urgency of required action. The main decision-making body of the Framework is the so-called Conference of Parties or COP.

It is responsible for monitoring and reviewing the implementation of the UNFCCC, its legal instruments and takes the decisions needed to implement the Convention. All the states and territories, i.e. the Parties that are part of the UNFCCC are represented at the COP. Currently the number of Parties stands at 197 (source: UNFCCC).

The COP meets annually and is hosted in a different state or at the headquarters of the UNFCCC in Bonn, Germany. The first COP took place in Berlin in 1995, while the most recent gathering, the COP 24, was held in Katowice, Poland last year.

Catalysing climate action – the COP in Paris 2015

Without going through the protracted and complex history of the UNFCCC since its beginnings, the remainder will focus on the climate negotiations since the COP 21 in Paris. The Paris climate change conference in late 2015 brought the topic back onto the headlines of newspaper and the desks of political actors.

Before the Paris meeting international climate negotiations were at a standstill. Many nongovernmental organisation as well as the wider public urged the negotiators to arrive at a new international agreement.

The main achievement of the COP 21 in Paris was the negotiation of a global agreement on the reduction of climate change as a consensus of the representatives of the 196 attending parties. The key result of the Paris Agreement (source: UNFCCC) was to set the goal of limiting global warming to “well below 2 °C” compared to pre-industrial levels and achieve zero net anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions during the second half of the 21st century.

Just before the Paris COP, almost 150 national climate panels presented drafts of their national climate contributions also called “Intended Nationally Determined Contributions” (INDCs) In these drafts the steps and goals to reduce emissions post-2020 of the individual states were detailed.

According to the Paris Agreement, those INDCs or also “Nationally Determined Contribution” (NDCs) will be revisited and updated every five years beginning in 2023. This is part of a “global stocktake” in order to determine the success of the measures to reduce emissions. Certainly, the Paris Agreement was the outcome of a successful international negotiation (source: EU Commission).

What happened since 2015?

The COP 22 in Marrakesh stood under the light of coming up and writing a rule book for the implementation of the Paris Agreement. Subsequently, the COP 23 took place in Bonn under the presidency of Fiji. In conclusion, the participating nations agreed on steps for higher climate ambitions especially before 2020.

During COP 24 that took place in Poland in December 2018, further guidelines for implementing the Paris Agreement have been set. The operationalization of the Paris Agreement and greater international cooperation where also points being discussed.

Especially common rules for measuring and reporting emissions for comparing and revising the Paris Agreement have been discussed. However, many difficult questions, such as upscaling of existing commitments and financial aid for poor countries have been postponed to the next conference.

The Special report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C by the IPCC was also not welcomed outright due to objections from the fossil-fuel producing countries USA, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.

Next to the official COPs other international meetings also took up the climate change issue. Most prominently, the G20 meetings. In Osaka during June 2019, a similar climate deal has been signed by the representatives as during the previous G20 Meeting in 2018. The text of the 2019 G20 declaration did not change much from last year and can be read here.

Negotiations for the COP 25 already started

The next COP should take place in early December 2019 in Chile. However, due to the unrest in the South American country, the local government has canceled the Climate Summit on October 30, 2019. COP 25 will once again focus on how to extend the individual national commitments to limit global warming.

Meanwhile, more than 1000 experts and negotiators met in Bonn at the end of June 2019 to prepare for the COP 25. Again, the US and Saudi Arabia have not agreed to vote in favor of the IPCC’s 1.5 ° C report.

Specifically, no solutions has yet been presented on how to account for projects that reduce emissions abroad and how far those can be used to offset national emissions (source: Erneuerbare Energien).

The shortcomings of the Paris Agreement

Even if lauded a landmark agreement, the contributions the Paris Agreement will have to limit climate change are questionable. Foremost, the targets in the NDCs are voluntary and non-binding. There are no enforcement mechanisms except a “name and shame” approach when it comes to the emission reduction goals.

Besides that the current NDCs, if duly followed and implemented, are rather bringing the world to a warming of 2.7 to 3.7 °C. This is compared to pre-industrial levels. It is much higher than the safe threshold as outlined by the IPCC (source: World Resource Institute).

Furthermore, President Donald Trump announced that the US will withdraw from the Paris Agreement. Thereby they would be leaving one of the biggest polluters out of the Agreement.

Climate finance far behind

Wealthy countries pledged to provide $100 billion per year from 2020 to poorer nations as part of international climate finance. However rules on this financing are still being negotiated about (source: insideclimatenews). This means an important way of addressing climate change in developing countries is not in place yet or at least underdeveloped.

A study of development organisation Oxfam showed that less than half of the $100 billion have been pledged as of now, while only about $20 billion was climate finance in a strict sense (source: the Guardian). Climate finance and the contribution of the developed nations thus are far behind the aspirations of the Paris Agreement.

Emissions further on the rise since 2015

The reality of global emissions speaks for itself, in addition to the protracted negotiations about financing climate protection measures and the limitation the Paris Agreement has in terms of its enforcement mechanisms.

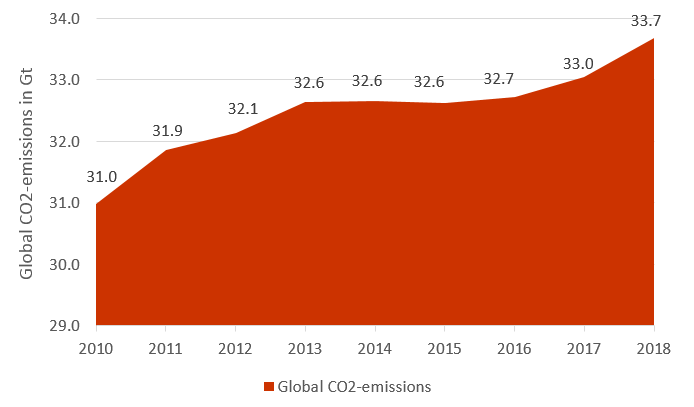

Since 2010, global anthropogenic CO2-emissions grew by 2.7 Gt, an equivalent of more than three times Germany’s annual emissions. While a plateau of CO2-emissions was noticeable from 2013 to 2015, since then emissions grew fast again, as figure 1 shows.

With 0.65 G,t the surge last year constituted the largest increase of CO2-emissions since 2010. It brought cumulative emissions to 33.7 Gt. While emissions ought to be declining rapidly in order to be consistent with a 1.5 or even a 2 degree world, the current global emission trajectory leads to climate disaster despite the Paris Agreement (source: Climate Action Tracker).

The flipside is obvious however. Without a global agreement and negotiations, along with the difficult, protracted and slow decision-making, climate protection might not feature on the international agenda prominently enough to derive any meaningful action.

What do you say on this subject? Discuss with us!