Who are the players in the electric car charging business? When it comes to pure charging station operation, three players emerge: the charge point operator (CPO), the e-mobility provider (EMP) and the electricity supplier. Let’s take a closer look at the individual roles.

Charge Point Operator

The CPO is responsible for the installation, service and maintenance of the charging station. He is the manager of the charging infrastructure, so to speak. The CPO does not have to be the owner or investor of the charging station at the same time, there are also lease models, for example.

He is responsible for procuring electricity for the charging station. This makes the charging station the final consumer within the meaning of the EnWG. There it says in § 3 No. 25 “[…] also the power consumption of the charging points for electric vehicles is equal to the final consumption […]”.

As already mentioned in part 2 of our series on e-mobility and confirmed here once again: The energy industry regulation important for final customers ends behind the charging point.

In the course of the amendment of the EU’s internal electricity market directive, it is currently also being discussed whether operators of electricity distribution networks are allowed to own or operate charging stations at all. At the end of this year, an agreement should have been reached at EU level.

According to Article 33, electricity distribution network operators should be excluded from the construction and operation of charging stations as a matter of principle. This would however ignore two facts: the technical and energy industry experience of municipal utilities and their ability to take local load peaks into account when planning grid or charging stations.

E-Mobility Provider

The EMP enables access to the charging infrastructure. This includes, for example, issuing the charging cards. With this card, the electric vehicle owners identify themselves at the charging station in order to start a charging process. He is the customer’s contact when it comes to tariff structures or the handling of charging processes.

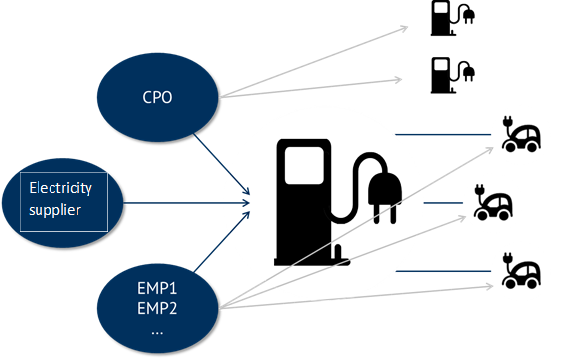

The backend is the technical infrastructure behind EMP and CPO through which the two roles interact. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

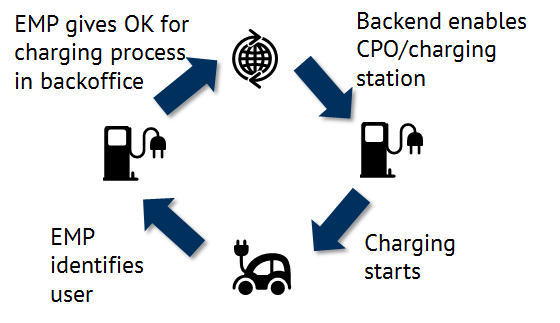

After a user has requested to charge at the charging station, the EMP identifies the user by means of his charging card or log-in at the charging terminal. The EMP enables the loading process in the backend. Now the CPO can start the charging process and the charging station is enabled. The process starts.

Electricity supplier

The electricity supplier supplies the charging station with the contractually agreed quantity of electricity. Since the charging station operator is the final consumer within the meaning of the EnWG, the charging station can only be supplied by one electricity supplier. Consequently, an e-mobilist cannot have “his” electricity supplied to another charging station.

Figure 2 shows the various players in the charging infrastructure. The classic energy industry regulation ends with the charging cable to the electric car.

The crux: measuring point operation

In the meantime, mobile metering has made it possible to operate measuring points for single e-mobility customers. A mobile measuring device is carried in the electric vehicle or in a separate charging cable.

The communication unit in the measuring device transmits the charged quantity of electricity to the operator of the charging station. This would make it possible, unlike previously mentioned, to be supplied by any power supplier while charging at different charging stations.

However, if this option is used, the operator of the mobile metering system becomes the metering point operator and therefore needs a contract with the local grid operator. If he wants to use his system in different grid areas, he needs a contract with the local network operator in the respective distribution grid area.

Although the mobile measuring equipment conforms to calibration law and is also justified by EnWG, MsbG and LSV, it is a complex subject. According to the new market role model, a fixed measurement location is assigned to the respective market location.

By carrying the measurement unit, the measurement location becomes mobile and can therefore no longer be clearly assigned to a market location. This requires a series of contracts between the various players. Increased standardization and automation of these procedures and processes would help to reduce complexity. This could make e-mobility roaming a reality.

Is the e-mobility business model profitable?

It looks like gold-rush atmosphere: You can see charging stations from the local public utility or one of the major energy providers popping up in every city. But are these systems really profitable or is it (still) a negative business case for the operators?

In Innogy’s half-year report, losses of EUR 16 million were reported in the “eMobility” area (source: Energate). With investments of EUR 28 million and higher employee numbers, Innogy shows that the Group considers electric mobility to be a strong growth market.

In addition to investments in the “eMobility” division, investments are also being made in young companies so that they can participate in technological developments at an early stage. At the beginning of the next decade, it is expected to reach the profit zone. Innogy’s business figures are an example of the chicken-and-egg problem of electric mobility.

The investments in charging stations and electric cars are mutually dependent; without charging stations nobody buys an electric car, without electric cars there is no investment in charging stations. Or in the case of innogy: the e-mobility providers first have to invest high up-front costs in order to be able to skim off profits years later.

The German Institute of Economics (IW) has also examined this problem in a brief analysis (source: IW). According to the IW, three electric cars in large German cities share one charging point. As a result, a charging station does not pay for itself through the sale of electricity alone, despite state subsidies during construction.

Operators of public charging stations would therefore also have to position themselves with additional services in order to generate additional income. For example N-ERGIE: Together with ABL and Mantro, the regional supplier from Nuremberg founded the joint venture “emonvia GmbH” (source: Electrive).

The joint venture wants to position itself as a service provider for other companies with a high mobility requirement and offers the operation of charging stations (monitoring, billing, integration of fleet management, load and charge management) as a service. Another example of additional benefits is offered by Aldi Süd: free charging at charging stations in the branch’s car parks. This makes the grocery discounter attractive for electric motorists who both want to shop and charge their cars.

However, the focus here is not on “charging station operation” as a business model, but on “charging station operation” as an additional service offering for customers (source: Aldi Süd).

These examples show that business models for electric mobility go far beyond simply setting up charging stations.

What do you say on this subject? Discuss with us!